Prisons have long been presented as institutions of justice, designed to protect society by rehabilitating criminals and deterring crime. However, beneath this noble facade lies a far more sinister reality. The history of mass incarceration reveals that prisons have often been used as tools of economic exploitation, racial oppression, and political control. To understand why prisons truly exist, we must examine their historical origins, their transformation into a profit-driven industry, and their disproportionate impact on marginalized communities.

The Birth of Incarceration: A Tool of Control

The concept of incarceration as a form of punishment is relatively modern. Ancient societies relied more on corporal punishment, exile, or execution rather than confinement. The prison system as we know it began to take shape in the 18th and 19th centuries with the rise of the penitentiary system, particularly in Europe and the United States. Early prisons were established with the promise of reforming criminals through isolation and hard labor.

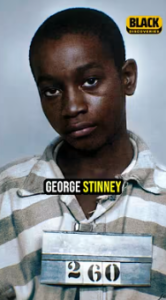

However, from their inception, prisons were used to control the lower classes, the poor, and racial minorities. In the U.S., for instance, the prison system was directly linked to the institution of slavery. After the Civil War, the Thirteenth Amendment abolished slavery “except as punishment for a crime.” This loophole allowed Southern states to criminalize newly freed Black Americans through “Black Codes”—laws that targeted them for minor infractions such as loitering or vagrancy. Once imprisoned, they were leased to private companies in a system known as “convict leasing,” essentially re-enslaving them under the guise of criminal justice.

The Rise of Mass Incarceration: Politics and Profit

Throughout the 20th century, prisons became increasingly entangled with politics and profit motives. The “War on Drugs” policies of the 1970s and 1980s, championed by Presidents Richard Nixon and Ronald Reagan, dramatically escalated incarceration rates. Harsh sentencing laws, including mandatory minimums and “three strikes” rules, disproportionately targeted Black and Latino communities. Nonviolent drug offenses led to lengthy prison terms, fueling the exponential growth of the prison population.

Simultaneously, the prison-industrial complex emerged, turning incarceration into a multi-billion-dollar industry. Private prison corporations such as Corrections Corporation of America (now CoreCivic) and GEO Group began profiting from mass incarceration, lobbying for stricter laws and tougher sentencing guidelines to ensure a steady stream of prisoners. These corporations benefit from cheap prison labor, often paying inmates mere cents per hour to produce goods for major companies. This system echoes the convict leasing programs of the post-slavery era, reinforcing the notion that incarceration is less about justice and more about exploitation.

The Disproportionate Impact on Marginalized Communities

Mass incarceration has overwhelmingly affected marginalized communities, particularly Black and Latino populations. Despite similar rates of drug use across racial lines, Black Americans are significantly more likely to be arrested, convicted, and sentenced to longer prison terms than their white counterparts. The criminal justice system operates with deep-seated racial biases that perpetuate cycles of poverty and disenfranchisement.

Moreover, the prison system extends beyond incarceration. Once released, former prisoners face lifelong consequences, including difficulty finding employment, housing discrimination, and loss of voting rights in many states. This systemic oppression ensures that marginalized individuals remain trapped in a cycle of poverty, increasing their likelihood of re-incarceration.

A Call for Change: Rethinking Justice

If prisons were truly about rehabilitation, the U.S. would not have the highest incarceration rate in the world, nor would recidivism rates remain so high. Instead, the current system prioritizes punishment over rehabilitation and profit over justice. There is an urgent need to rethink our approach to criminal justice.

Alternative models, such as restorative justice and community-based rehabilitation programs, have proven to be more effective in reducing crime and recidivism. Countries like Norway, which focus on rehabilitation rather than punishment, have significantly lower crime rates and recidivism. Investing in education, mental health services, and social programs can prevent crime more effectively than mass incarceration ever could.

Conclusion

The prison system is not merely a mechanism for justice but a tool historically used to control, exploit, and oppress. From convict leasing to the modern prison-industrial complex, incarceration has been shaped by economic and racial injustices rather than a genuine commitment to public safety. If we are to address the deep-rooted issues within this system, we must first acknowledge its dark history and work toward a justice model that prioritizes rehabilitation, equality, and human dignity over profit and punishment.